Federal University of Agriculture Abeokuta

Federal University of Agriculture Abeokuta

Author

Author  Correspondence author

Correspondence author

International Journal of Molecular Ecology and Conservation, 2012, Vol. 2, No. 4 doi: 10.5376/ijmec.2012.02.0004

Received: 17 Sep., 2012 Accepted: 24 Sep., 2012 Published: 31 Oct., 2012

Oduntan et al., 2012, Economic Damages of Primates on Farmlands in Old Oyo National Park Neighborhood, International Journal of Molecular Ecology and Conservation, Vol.2, No.4, 21-25 (doi: 10.5376/ijmec.2012.02.0004)

This paper investigated an estimated amount of losses incur due to damages caused by Primates on farmlands and the methods of control in the neighbourhood of Old Oyo National Park, Nigeria. Primary data were collected and used for the study. Data were collected through the use of open-ended questionnaires administered to all the affected farmers in the study area. Non-probability snowballing method was used in locating and sampling affected farmers. The result revealed that an estimated average of ₦3 979.18±5.79, ₦3 981.33±3.67, ₦3 974.60±6.85, ₦3 905.85±6.32 worth of Yam tubers were lost by each farmer in Abanla, Imodi, Budo Alhaji and Fomu villages respectively. Also, an estimated average of ₦67 656.35±420.90, ₦68 248.14±500.97, ₦66 094.73±482.22, ₦67 817.90±554.17 worth of maize were lost on farmlands by each farmer at Abanla, Imodi, Budo Alhaji and Fomu villages respectively. In addition, an estimated average of ₦4 780.13±1.53, ₦3 993.09±4.50, ₦5 834.50±4.48, ₦5 321.33±3.99 worth of cassava plants or tubers were lost to primate in the respective villages mentioned. Furthermore, most of the respondents (43.33%, 50%, 39.3% and 46.15% at Abanla, Imodi, Budo Alhaji and Fomu respectively) engaged the use of fire arms in the control of Primates on their farmlands. Results also shows that three basic techniques used in controlling damages by Primates in the study areas are; fire arms, traps and chasing. Recommendations were made based on the outcome of the study.

Problem animal control, world-wide is a controversial subject and there is considerable debate regarding the removal of problem species, particularly in the more developed countries where possible ramifications to the ecology have been realized. All animals (be it herbivores, carnivores, omnivores, birds, insect, pisces etc.) form a vital component of the workings of a stable and balanced environment. In such undisturbed or natural ecosystem, they interact with one another, holding each other in balance. The role of wildlife in the ecological set up especially as pertaining to maintaining an ecological balance in the function and structure of an ecosystem can be over emphasized. A study of the transfer or transmission of energy through the ecosystems in the food chain and food webs shows that the functioning of the systems and sustenance of life in it is performed by all the components making up the ecosystem (Oduntan, 2006, unpublished data). However, some wildlife are regarded as pests because they damage some components of the habitat that are of economic interest to man and this may seriously impair man’s effort to produce food (Evans, 1987). Hamilton et al (1987) defined a pest species has any organism, animal or plant which harms or cause damage to man, his animal, crop and that even cause annoyance to him. Wildlife damage problems varies from place to place depending on the species involved, with varying type and level of damage to cultivated crops in the field resulting in decreases in the quantity and quality of food available for consumption as well as poor income and standard of living of farmers (Johnson, 1986).

Throughout the world, primates have come in conflict with humans; they often damage farmer’s crops, livestocks and some have also been known to injure or even kill people (Newman, 2004; Groves, 2005). They may also feed upon the same natural foods that people and livestock eat, thus competing with humans for these resources. Newman (2004) described the Baboon as the most common crop-raider. They go in groups to damage large areas of crops in a single sitting. Primates are highly intelligent animals which work as a team. Groves (2005) reported that some will look out for the farmers while the others feed and they do it interchangeably. This enables them to damage greater areas of crops than animals that feed alone.

Just knowing that farmers are experiencing crop losses due to wildlife raiding may not necessarily give adequate information to determine the impact on local communities or individuals. Data on types of crop damaged as well as estimated quantities and amount of crop lost are of importance for effective management of agriculture-wildlife conflict. This paper investigated types of crop damaged by Primates in the neighbourhood of Old Oyo National Park as well as estimated the amount of losses incur due to damages caused by Primates on farmlands in the same study area.

1 Survey methods

1.1 Study area

The study was carried out in villages bordering Old Oyo National park, Nigeria. Old Oyo National Park (OONP) is one of the National parks of Nigeria, located across northern Oyo State and southern Kwara State, Nigeria. The park is easily accessible from southwestern and northwestern Nigeria. The nearest cities and towns adjoining Old Oyo National Park include Saki, Iseyin, Igboho, Sepeteri, Tede and Igbeti which have their own commercial and cultural attractions for tourism.

The park takes its name from Oyo-lle (Old Oyo), the ancient political capital of Oyo Empire of the Yoruba people, and contains the ruins of this city. Oyo Ile was destroyed in the late 18th century by Ilorin and Hausa/Fulani warriors at the culmination of the rebellion of Afonja, commander of Oyo Empire's provincial army for which he allied himself with Hausa/Fulani Muslim jihadists. The National Park originated in two earlier native administrative forest reserves, Upper Ogun established in 1936 and Oyo-lle established in 1941. These were converted to game reserves in 1952, then combined and upgraded to the present status of a National Park. The park covers 2 512 km2, mostly of lowland plains at a height of 330 m and 508 m above sea level. The southern part is drained by the Owu, Owe and Ogun Rivers, while the northern sector is drained by the Tessi River. Outcrops of granite are typical of the north eastern zone of the park, including at Oyo-lle, with caves and rock shelters in the extreme north. The central part of the park has scattered hills, ridges and many rock outcrops that are suitable for mountaineering. The Ikere Gorge Dam on the Ogun river provides water recreation facilities for tourists.

1.2 Methodology

Old Oyo National Park comprises of a whole lot of communities bordering the 5 ranges (which are: Oyo Ile, Sepeteri, Tede, Yemoso and Marguba Ranges) of the park. However, only two ranges were used for this study based on the location and distribution of primate within the park. They are: Marguba Range (comprising of Abanla and Imodi villages) and Sepeteri Range (comprising of Budo Alhaji and Fomu villages). Thus the four villages mentioned above were used for the study. This study was conducted in January, 2012 and data were collected for 2011 planting seasons.

1.3 Data collection

Primary data were collected and used for the study. Data were collected through the use of open-ended questionnaires administered to all the affected farmers in the study area. One hundred and thirteen (113) questionnaires were administered in all. Non-probability snowballing method was used in locating and sampling affected farmers.

Snowball sampling technique is a non-probability sampling method used when the desired sample characteristic is rare. It may be extremely difficult or cost prohibitive to locate respondents in these situations. Snowball relied on referrals from initial subjects to generate additional subjects, i.e. the interviewer identified one or more respondent(s) among the association who referred the interviewer to another respondent and the chain continue like that until the sample is exhausted or obtained. Since the study areas are small communities, all affected farmers were interviewed until no new referral was made.

Descriptive statistics such as frequency tables, percentages and bar chart were used for analysis.

2 Results and Discussions

2.1 Socio-economic structure

The study (Table 1) shows that majority of the farmers were male (62.00%) and with no formal education (48.70%). This result was in line with the earlier findings of Oduntan et al (2008) which stated that 72.00% and 75.00% of farmers in communities bordering OONP were male and without formal education respectively. Past researchers have found that farmers with formal or higher education level are more likely to recognize and be cautious of harmful environmental practices or pest control methods (Jacobson et al, 2006). Also, 73.45% of the farmers are married, while 69.00% had a family size of between 7 and above. Previous studies (Akinyemi and Oduntan, 2004; Oduntan et al., 2012, accepted) revealed that families with many members will likely have more economic pressure and struggling to uplift their living standard.

2.2 Financial implication of wildlife-crop damages in the study area

Table 2 shows the average value of crops lost to Primates in the study area. The result revealed that an estimated average of ₦3 979.18±5.79, ₦3 981.33±3.67, ₦3 974.60±6.85, ₦3 905.85±6.32 worth of yam tubers were lost by each farmer in Abanla, Imodi, Budo Alhaji and Fomu villages respectively. The result also showed that an estimated sum of ₦43 771.20, ₦59 720.17, ₦59 619.06 and ₦54 682.21 worth of yam plants or tubers were lost to primate invasion on a total of 55 farmlands in Abanla, Imodi, Budo Alhaji and Fomu respectively.

In addition, an estimated average of ₦67 656.35±420.90, ₦68 248.14±500.97, ₦66 094.73±482.22, ₦67 817.90±554.17 worth of maize were lost on farmlands by each farmer at Abanla, Imodi, Budo Alhaji and Fomu villages respectively. The result revealed an estimated sum of ₦473 594.40, ₦409 488.90, ₦396 568.40 and ₦440 816.40 worth of maize cobs or plants were lost to primate preying on 47 farmlands in Abanla, Imodi, Budo Alhaji and Fomu respectively (Table 2).

Furthermore, while an estimated sum of ₦11949.04,, ₦7983.09, ₦11669.21 and ₦7982.00 worth of cassavaure plants or tubers were lost to primate invasion on a total of 10 farmlands in the respective villages mentioned; an estimated average of ₦4 780.13±1.53, ₦3 993.09±4.50, ₦5 834.50±4.48, ₦5 321.33±3.99 worth of cassava plants or tubers were lost to primate in Abanla, Imodi, Budo Alhaji and Fomu respectively as shown in Table 2.

This study shows that not many cassava farmlands or plants were affected by primates, when compared with other food crops that were affected in the study areas. This can be as a result of comments made by farmers in the study site that unlike maize and yam, primate rarely eats cassava tuber or plants, which may be as a result of high percentage of cyanide in cassava. Farmers’ comments in the study area further revealed that angered, provoked or wounded primates often intentionally destroyed farm crops, uprooting tubers and maize plants on farmlands.

In general, a total of ₦217 792.64, ₦1 720 467.70 and ₦39 583.34 worth of yam, maize and cassava farmlands were altogether respectively destroyed in villages prone to primates attack within the Old Oyo National Park ranges. Oduntan et al (2009) concluded that destruction of crop by wild animal species hardened farmers' attitude against wildlife conservation. Loss of thousands and millions of Naira of food crops in villages of a nation where 70.80% of the population are living on less than one dollar a day and 92.40% on less than two dollars a day (UNICEF, 2006, http://www.unicef.org/wcaro/ Countries_1320.html.) can further impoverished people living in such areas. Akinyemi and Oduntan (2004) argued that killing of wild animal is not an activity in which people engage in for the purpose of deriving leisure from it, rather it is an activity associated in one form or the other with the upliftment of living standard of people.

2.3 Primate damage control

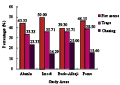

Results also shows (Figure 1) that three basic techniques were in use in controlling damages by primates in the study areas. The techniques include the use of traps, chasing and the use of fire arms. While some of the respondents claimed that they only fire gun shot into the air to scare the animals away; some others disclose that there are occasions when many of the primate had been killed either intentionally or otherwise. This finding however, corroborates that of Oduntan et al (2009) where unfavorable attitude of farmers to wild animal species was traced to the information gathered on the estimated number of farmers that lost crops to wild animal species and the rate of occurrence.

The result further revealed that most of the respondents (43.33%, 50.00%, 39.30% and 46.15% at Abanla, Imodi, Budo Alhaji and Fomu respectively) engaged the use of fire arms in the control of Primates on their farmlands. Distribution on the use of fire arms was closely followed by use of traps with a representation of 33.33%, 35.71%, 35.71% and 38.50% of respondents in the respective villages. However, both the use of fire arms and traps are known to be unfriendly to wildlife conservation as it can either lead to outright killing of wild animal or rendering them wounded. It can be deduced from this result that if this methods of controlling primate invasion on farmlands are not quickly checked, the animals may soon be wiped out in the National Park.

3 Conclusions and Recommendation

This study revealed that farmers in the neighboring villages of OONP losses several amount of money to damages caused by primates on their farmlands. Majority of the farmers however resulted into use of fire arms and traps in controlling primate damages on their farmlands. There is need to educate the farmers on the importance of using wildlife damage control that support wildlife conservation such as cultivating on land unit that are clearly out of wild animal ranges to minimize damages. Nigerian government should also encourage farmers by compensating for losses incur on farmlands due to wild animal damages, as a means of encouraging favorable attitude of farmers toward wild animal conservation.

References

Akinyemi A.F., and Oduntan O.O., 2004, An evaluation of the effect of conservation legislation on wildlife offences in Yankari National Park, Bauchi state, Nigeria Journal of Forestry, 34(2): 28-35

Evans J., 1987, The porcupine in the Pacific north-west, In: Baumgartner D.M., Mahoney R.L., Evans J., Caslick J., and Brewer D.W., Co-chair an. damage manage. in Pacific northwest for. coop. ext. Serv., Washington State University, Fullman, pp.75-78

Hamilton J.C., Johnson R.J., Case R.M., Riley M.W., and Stroup W.W., 1987, Fox squirrels cause power outages: an urban wildlife problem, In: Holler N.R. (ed.), Proceedings of the 3rd Eastern Wildlife Damage Control Conference, 18~21, October, 1987, Gulf Shores, Alabama, USA, pp.228

Jacobson S.K., Sieving K.E., Jones G., McElroy J., Hostetler M.E., and Miller S.W., 2006, Farmers' Opinions about Bird Conservation and Pest Management on Organic and Conventional North Florida Farms, University of Florida IFAS Extension, University of Florida, USA, pp.1-8

Johnson R.J., 1986, Wildlife damage in conservation tillage agriculture: a new challenge, In: Salmon T.P. (ed.), Proceedings of the 12th Vertebrate Pest Conference, 3, Janaury, USA, pp.127-132

Groves C., 2005, GENUS Papio, In: Wilson, D.E., and Reeder D.A.M. (ed.), Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference, 3rd, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp.166-167

Newman T.K., Jolly C.J., and Rogers J., 2004, Mitochondrial phylogeny and systematics of baboons (Papio), American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 124 (1): 17-27

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.10340

PMid:15085544

Oduntan O.O., Ojo V.A., and Odunaiya O., 2008, Conservation legislation and wildlife offences in old Oyo national park: contribution of stakeholders, Obeche Journal, 27(1): 59-65

Oduntan O.O., Akinyemi A.F., and Ayodele I.A., 2009, Attitude of farmers to wild animals in Hadejia-Nguru wetlands: causes and implications, Obeche Journal, 28(1): 12-16

Oduntan O.O., Akintunde O.A., Oyatogun M.O.O., Shotuyo A.L.A., and Akinyemi A.F., 2012, Proximate Composition and Social Acceptability of Sun-Dried Edible Frog (Rana esculenta) in Odeda Local Government Area, Nigeria, Journal of Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry, Nassarawa State University, Nigeria. MS-12S+130, Vol 6(1) (accepted)

. PDF(217KB)

. FPDF

. HTML

. Online fPDF

Associated material

. Readers' comments

Other articles by authors

. Oladapo Oduntan

. Oluyinka Akintunde

. David Ogunyode

. Oluwatosin Adesina

. Abiodun Oladoye

Related articles

. Wildlife

. Conservation

. Damage control

. Conflicts

Tools

. Email to a friend

. Post a comment

.png)

.png)